Vadose Zone Inversions

Applications of Richards Equation

4.1Introduction¶

Characterizing hydraulic parameters can be completed using direct methods, which require laboratory samples to be taken. However, because much of the vadose zone consists of unconsolidated materials, these invasive measurement techniques may disturb the soil properties, especially porosity and water content Deiana et al., 2007. Furthermore, these point measurements may not represent the entire hydrologic setting and cannot observe the vadose zone processes in situ. Geophysical methods, however, can be used to generate spatially extensive estimates of physical properties, which can be related, through empirical relations, to hydrogeologic properties, such as hydraulic conductivity. We can use geophysical inversions, such as direct current resistivity, to image the electrical conductivity. The electrical conductivity is related to the soil moisture content and the fluid electrical conductivity. This relation is empirically described through Archie's equation Archie, 1942:

where is the bulk electrical conductivity of the fluid filled soil or rock, is the electrical conductivity of the fluid, is the porosity, and is the effective saturation. The exponents, and , and scaling factor, , are empirical fitting parameters, which are occasionally referred to as the cementation exponent, the saturation exponent, and the tortuosity factor, respectively. Archie's equation, which must be further modified in the presence of clays, has three empirical parameters that are either unknown or poorly constrained. If the imaging for electrical conductivity is completed in a time-lapse experiment, we can capture changes of moisture content over time due to fluid movement. In the vadose zone, the moisture content is the time-stepping term in the Richards equation, which is related to the pressure head through another empirical relation (e.g. the van Genuchten-Mualem empirical relations). Given estimates of saturation, an inversion can be formulated for hydraulic parameters using the Richards equation (Chapter \ref{ch:richards}). The van Genuchten empirical model has five parameters (, and ) that are commonly estimated in laboratory experiments. We can use these hydraulic parameters in groundwater models to make predictions and decisions about groundwater processes.

In summary, we can use geophysical measurements to make time-lapse images of water content, which, in turn, can be used in conjunction with a groundwater simulation to invert for hydraulic properties (cf. Hinnell et al. (2010)). Throughout this process, we require multiple empirical parameterizations as well as extensive hydrogeologic knowledge, including knowledge of boundary and initial conditions. In Binley et al. (2002), a cross-well tomography experiment was conducted using radar and DC resistivity over the course of a vadose zone tracer test. The center of mass of the tracer was found and tracked over time using the geophysical imaging and subsequent empirical interpretation as water content changes, . A separate groundwater simulation was completed using the Richards equation to estimate the saturated hydraulic conductivity, which was assumed to be homogeneous and isotropic and was determined through "trial and error" because "no automatic data matching was possible" due to the size of the numerical simulation. Similarly, in Deiana et al. (2007), "only the saturated hydraulic conductivity was modified by trial and error to match field data." In this case, anisotropy was introduced to further fit the results obtained by matching the infiltration experiment. Similarly, when investigating coupled hydrogeologic and geophysical simulation, Hinnell et al. (2010) notes that the parameterization was "simpler than reality to make numerical inversion tractable" and that the computational power necessary for a stochastic "approach limits widespread application and use of the hydrogeophysic[s]." The lack of algorithms that formulate and solve the inverse problem for the Richards equation is a hurdle in the analysis and joint quantitative analysis of hydrologic and geophysical data. In Chapter \ref{ch:richards}, we presented a formulation that reduced a number of these barriers to efficient large-scale parameter estimation. However, the numerical ability to invert for five distributed parameters at once is not immediately practical.

In this chapter, we will use the algorithm and formulation of the inverse problem developed in Chapter \ref{ch:richards} to investigate a distributed multi-parameter inversion in both one and three dimensions using water content data. The goal of this work is: (a) to explore the nonlinearities and couplings in the van Genuchten functions; and, (b) to demonstrate that it is now possible to complete an inversion for distributed hydraulic parameters in a large-scale 3D simulation. We also refer the reader to Appendix \ref{ch:extensions}, where we expose the assumptions in a forward simulation framework to manipulation and estimation. This appendix also demonstrates multiple geologic- and physics-based parameterizations that can be used to embed knowledge between diverse disciplines.

4.1.1Attribution and dissemination¶

This work extends the previous chapter in terms of applications, but it also extends the forward simulation framework and the inversion framework that is necessary to flexibly invert for multiple distributed parameters at once. We abstracted the necessary advancements in the framework from the organization and implementation of electromagnetics inversions in both time domain and frequency domain. The forward simulation framework used for all numerical examples is derived from this cross-disciplinary, collaborative work in the Richards equation and electromagnetics. This work is presented in Heagy et al. (2016) for eight formulations of Maxwell's equations for geophysical simulations and inverse problems. Appendix \ref{ch:extensions} shows an adaption of the forward simulation framework for the Richards equation, along with a number of other collaborative case-studies that build upon or extend this work. The library for implementing the numerical methods and inverse formulation is contained in SimPEG.FLOW.Richards (https://

4.2Empirical relationships¶

The Richards equation relies upon the correct parameterization of both the water retention curve and the hydraulic conductivity function. A number of empirical models have been proposed to describe these functions, including Brooks & Corey (1964), Haverkamp et al. (1977), Genuchten (1980), and Mualem (1976). All of these empirical models are loosely based on the physical interpretation of fitting parameters; however, this basis can be misleading and it has been shown that many parameters have no physical meaning and should be considered empirical shape factors Schaap & Leij, 2000. These functions have also been interpreted as splines, which can be helpful in the inverse formulation Bitterlich & Knabner, 2002. The van Genuchten model, introduced in Chapter \ref{ch:richards}, is written as:

where

Here, and are the residual and saturated moisture contents, is the saturated hydraulic conductivity, and are fitting parameters, and is the effective saturation. The pore connectivity parameter, , is often taken to be , as determined by Mualem (1976).

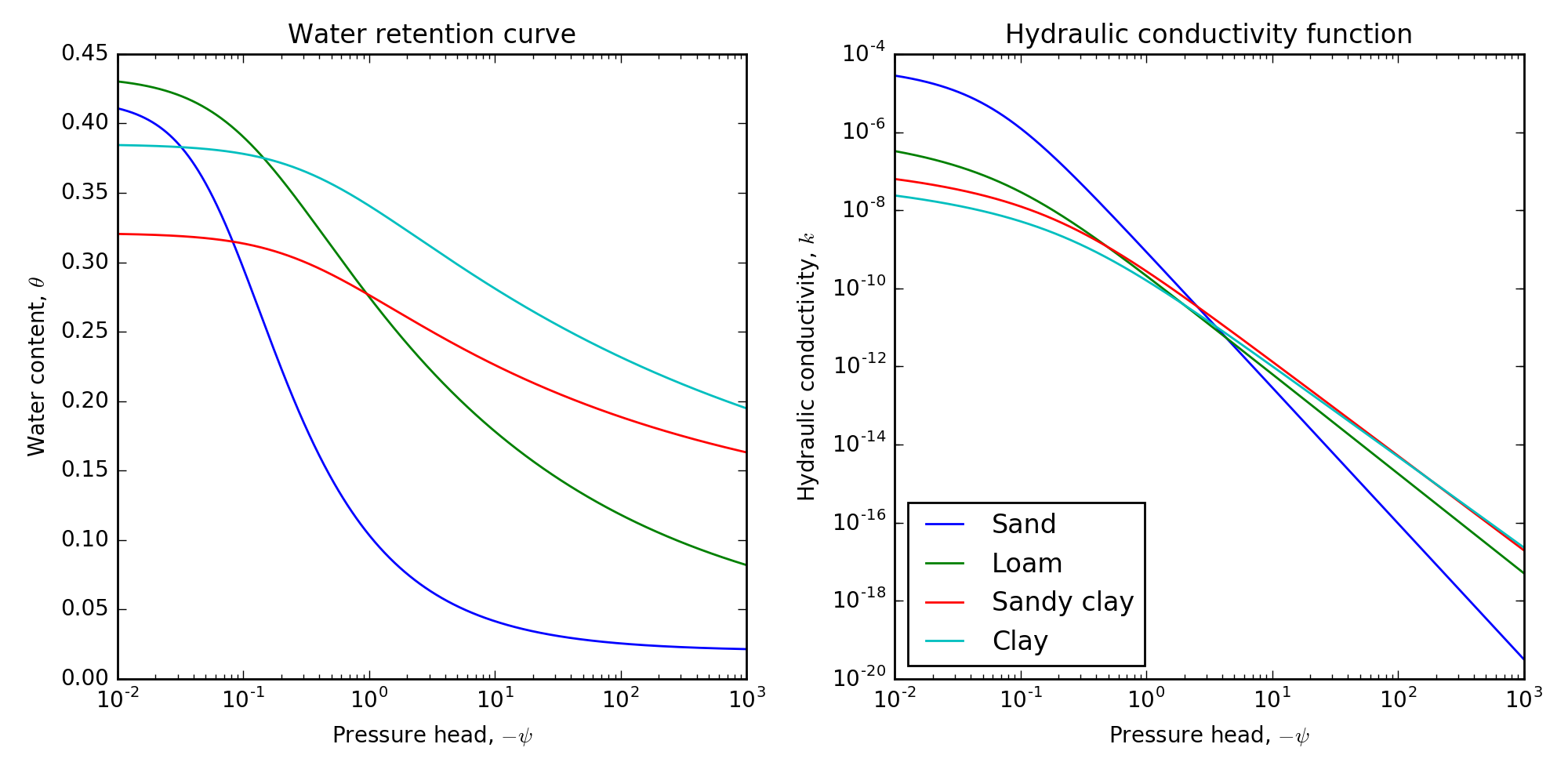

These curves are unknown at every point in space in the inverse problem. We will use a number of canonical parameters for the van Genuchten empirical relation to look at the water retention curve and the hydraulic conductivity function; Table 4.1 shows the values for these parameters. The soil-naming scheme refers to the proportions of sand, silt, and clay. Figure 4.1 shows the functions over a range of negative soil water potentials for four soil types (sand, loam, sandy clay, and clay). The soil water potential varies over the domain . When the value is close to zero (the left hand side), the soil behaves most like a saturated soil where and . As the water potential becomes more negative, the soil begins to dry, which the water retention curve shows as the function moving towards the residual water content (). The parameters and determine the slope and shape of this transition. In Figure 4.1, we see that the water retention curve for sand has a high saturated water content but rapidly changes to a low residual water content. For clay, this transition, with respect to the soil water potential, is much more gradual. This difference has to do with the small size of the pores in clay and their ability to retain water, even at high suctions. This difference is reflected in the hydraulic conductivity function: when close to saturated conditions, sand has the highest hydraulic conductivity, however, as the soil dries, the hydraulic conductivity of sand decreases rapidly and becomes relatively lower than a loam or clay with the same water potential.

Table 4.1:Canonical soil parameters for the water retention and hydraulic conductivity curves Van Genuchten et al., 1991

| Soil Type | (1/m) | (m/s) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sand | 0.020 | 0.417 | 13.8 | 1.592 | 5.8e-05 |

| Loamy sand | 0.035 | 0.401 | 11.5 | 1.474 | 1.7e-05 |

| Sandy loam | 0.041 | 0.412 | 6.8 | 1.322 | 7.2e-06 |

| Loam | 0.027 | 0.434 | 9.0 | 1.220 | 1.9e-06 |

| Silt loam | 0.015 | 0.486 | 4.8 | 1.211 | 3.7e-06 |

| Sandy clay loam | 0.068 | 0.330 | 3.6 | 1.250 | 1.2e-06 |

| Clay loam | 0.075 | 0.390 | 3.9 | 1.194 | 6.4e-07 |

| Silty clay loam | 0.040 | 0.432 | 3.1 | 1.151 | 4.2e-07 |

| Sandy clay | 0.109 | 0.321 | 3.4 | 1.168 | 3.3e-07 |

| Silty clay | 0.056 | 0.423 | 2.9 | 1.127 | 2.5e-07 |

| Clay | 0.090 | 0.385 | 2.7 | 1.131 | 1.7e-07 |

Figure 4.1:The water retention curve and the hydraulic conductivity function for four canonical soil types of sand, loam, sandy clay, and clay.

In this chapter, we are interested in the inverse problem for the soil parameters, which controls the shape and intercepts of these two functions. To solve this problem systematically, we will first observe how the shape of these curves change as the empirical parameters are modified over the full empirical range. In Figure 4.2, we complete this process for the hydraulic conductivity function for the four soil types (sand, loam, sandy clay, and clay). The bounds show the change from that curve by varying a single parameter and holding the rest constant. The saturated hydraulic conductivity, , can move the entire curve up and down. The parameters and control the shape of the curve as the negative soil water potential increases. Figure 4.3 also shows the four soil types for the water retention curve. As expected in this case, controls the -intercept and controls the minimum value of the function. Again, the parameters and control the shape of the curve between the bounds of and . In this case, the parameter has much the same effect as ; Šimunek et al. (1998) notes this high correlation. Note that the parameters and are involved in both the calculation of and , which links these two curves in a physically reasonable way Bitterlich et al., 2004. Additionally, the low parameterization of these curves, when using the van Genuchten empirical relationship, means that changing one parameter has a global effect over the domain of the soil water potential, . When framing the inverse problem, a spline parameterization for each curve can alternatively be used. Although framing in this way decouples the two curves, we need to take care when extrapolating the results to moisture contents not covered by the bounds of the experiment and to ensure that the obtained curves are physically reasonable Bitterlich et al., 2004. To avoid these potential pitfalls of an inversion, we will use the van Genuchten empirical parameterization for the remainder of the experimentation.

![The hydraulic conductivity function showing bounds of the various parameters

K_s \in [1\times 10^{-7}, 1\times 10^{-4}], \alpha \in [2.5, 13.5], and n \in [1.1, 1.6]

for four canonical soil types of (a) sand, (b) loam, (c) sandy clay, and (d) clay.](https://cdn.curvenote.com/2ba28247-02f0-46a7-921d-40c255e4e10f/public/richards-k-fun-eec42e7c9af5240a8c8db36e696395a5.png)

Figure 4.2:The hydraulic conductivity function showing bounds of the various parameters , , and for four canonical soil types of (a) sand, (b) loam, (c) sandy clay, and (d) clay.

![The water retention function showing bounds of the various parameters

\theta_s \in [0.3, 0.5], \theta_r \in [0.01, 0.1], \alpha \in [2.5, 13.5], and n \in [1.1, 1.6]

for four canonical soil types of (a) sand, (b) loam, (c) sandy clay, and (d) clay.](https://cdn.curvenote.com/2ba28247-02f0-46a7-921d-40c255e4e10f/public/richards-theta-fun-01efbf92e85c78ef118c0506a8e0f3d0.png)

Figure 4.3:The water retention function showing bounds of the various parameters , , , and for four canonical soil types of (a) sand, (b) loam, (c) sandy clay, and (d) clay.

4.2.1Objective functions¶

To further explore the van Genuchten parameterizations, we will use a homogeneous sandy clay loam (: 1.2-06 m/s, : 3.6 1/m, : 1.25, : 0.068, : 0.33) in a small infiltration experiment. The boundary conditions on the top of a 40 cm deep soil profile are cm at cm and cm at cm. The Richards equation simulation is run for a time period of 22 hours with an exponentially increasing time step from 5 s to 60 s. Saturation data is collected at nine equally spaced locations from -2 cm to -34 cm. The water content data at each of the nine locations is sampled 23 times over the length of the experiment. This sampling differs from traditionally collected laboratory experiment data, which records water outflow, distributed pressure measurements (using tensiometers), or bulk soil moisture. The analysis here is completed with the assumption that distributed estimates of soil moisture are available from a geophysical method.

In the following sections, we will be estimating the van Genuchten parameters (, and ) from this water content data. In this section, we will visualize the objective function, norm of the data difference, around the true model to get a sense of the optimization problem for a homogeneous soil with this data. Even with a homogeneous soil, the objective function is in five-dimensional space, so both visualization and identification of local minima is difficult. Figure 4.4 shows ten profiles through the objective function. These profiles are created by varying two of the parameters while keeping all other parameters constant at the true values. A grid, over reasonable bounds of each parameter, requires 16,000 simulations and produces ten cross-sections of the five-dimensional space. The cross-sections of , , , and show well-defined objective functions that are convex along these planes. The structure of the objective functions for and , with respect to , shows a more elongated objective function with contours nearly perpendicular to the axis, which means that, while keeping constant in Figure 4.4h and Figure 4.4i, both and can vary over their respective ranges at similar objective function values. In Figure 4.4c, can also change while keeping constant at similar objective function values. Mawer et al. (2013) also notes low sensitivity to the parameter when inverting saturation estimates for homogeneous layers. In this case, we also see the contours of the objective function as perpendicular to the axis, which indicates low sensitivity to in this plane of the objective function (Figure 4.4e). In all cases, when is involved, except for the cross-section of , the objective function is elongated perpendicular to the axis. This perpendicular elongation means that there is high sensitivity to , which is not surprising given that our data is water content. Additionally, the boundary conditions of the experiment yield pressure head values in the entire domain between m and m, which is in the domain where has the greatest influence over the shape of the water content response to pressure head (Figure 4.3).

Figure 4.4:Objective function cross-sections plotted for all ten cross-sections through the five dimensional space of and . Each cross-section was simulated with simulations and compared using an data objective function. The results are shown in -scale.

This analysis of the objective function shows that all of the cross-sections around the global minima are convex (albeit highly elongated in some axes). If local minima exist, these are not located on cross-sections through the true soil parameters. However, as seen in Figure 4.2 and Figure 4.3, at a single soil water potential, a change in any parameter can raise or lower the functions for hydraulic conductivity and water content. If only a small portion of each curve is examined by the experimental setup (i.e. boundary and initial conditions and measurement locations), then the recovery of these parameters will be non-unique. In the following sections, we will release the assumptions of a homogeneous soil and investigate the recovery of distributed soil parameters in a one-dimensional soil profile.

4.3Layered soil profile¶

In this section, we will investigate our ability to recover the van Genuchten parameters of a layered soil. The general setup of this experiment continues to expand on the 40 cm deep soil profile examined in the previous section. In this case, however, we break up the soil profile into three layers: (1) silt loam from 0 cm to -15 cm; (2) loam from -15 cm to -25 cm; and, (3) sandy clay loam from -25 cm to -40 cm. Table 4.1 shows the values for the van Genuchten curves. Figure 4.5 shows the pressure head and water content fields as an image of the 1D soil profile over the length of the experiment. The boundary conditions are set to inhomogeneous Dirichlet with values of -5 cm at the top of the model and -41.5 cm at the bottom of the model. The infiltration front is observed as a pressure increase moving down through the soil profile. The pressure head field is continuous across layer boundaries, as is expected. We can translate the pressure head everywhere in time and space to a saturation profile over time using the known spatially heterogeneous van Genuchten parameters (Figure 4.5b). The most notable difference is the discontinuity between layers, which is mostly due to the differences in , although the parameters and and, to a lesser extent, , also influence these discontinuities. This figure shows the infiltration front as an increase in soil water content, which corresponds to the increase in pressure head. We end the experiment when the infiltration front reaches the bottom of the soil profile at 22 hours. The water content figure shows the measurement locations as equally spaced samplings from -2 cm to -34 cm. We took the measurements over the entire time-lapse experiment, as seen in Figure 4.6. There were 225 measurements for the entire experiment. We added 1% noise to the synthetic data, which the figure shows as . This noise is far below what can be expected in any geophysical recovery of the water content; however, by adding more noise, we must conversely reduce our expectations of recovering the true distributions. In this experiment, we are interested in what is possible to recover under the best of circumstances.

Figure 4.5:Fields from the numerical simulation of a layered one dimensional soil profile, showing (a) pressure head and (b) water content over the full time period. The soil types are shown as annotations on each figure, the spatial location of water content measurements are shown adjacent to the water content fields.

4.4Unconstrained joint inversion¶

To recover the van Genuchten parameters of , and , we will frame the problem as an unconstrained joint inversion for all parameters at once. This framing requires that the model, , contains all five parameters for every cell in the model and, in this case, has a length of 200. To get the model for hydraulic conductivity, for example, we use a projection matrix to select the appropriate rows of the model vector.

We can also complete other model parameterizations at this stage to embed other knowledge (Appendix \ref{ch:extensions}). For example, we expect the hydraulic conductivity to be logarithmically varying, so a model of can be created. This mapping, as well as the projection, must be taken care of in both the translation to the physical property values and the derivative. The entire mapping can be represented as , where is the parameter that is mapped from the model, . In the previous chapter, we only addressed the model derivative, with respect to saturated hydraulic conductivity. In this chapter, we also require the derivative of the water content curve as well as the derivatives with respect to each parameter in the van Genuchten relationships. The derivative for the water content curve requires attention in both the time stepping terms and in the conversion of the pressure head field to water content for inclusion in the measurement locations.

The inversion for all van Genuchten parameters at once can be written as a sum of weighted objective functions:

Here, refers to both model smoothness and smallness for each mapped parameter. The can be chosen independently for each parameter. The weightings have significant influence on the inversion; a poor choice of weighting can cause the optimization of the objective function to not converge. We chose the weightings for the inversion results presented by looking at the relative magnitudes of the model resolution matrix () around the starting model, (). The objective function weights that we used in this inversion were approximately the average sensitivity over the entire soil profile: =1e-3; =1; =1; =1e2; and, =5e3. The parameter was chosen by relatively weighting the data misfit and model regularization terms at 1:100 based on a coarse estimate of the major eigenvalue of each inversion component. We used a cooling schedule for that reduced by a factor of five every three iterations. The starting model used was a soil with the parameter values of the middle layer of the model: a loam, with the exception of the parameter, that was set to an initial value of six, which was the midpoint of the values presented in Table 4.1. We optimized the objective function with an inexact Gauss-Newton algorithm that used five conjugate gradient iterations for each step in the inversion. The data misfit function started with a value of 2.8e4, which was reduced two orders of magnitude to the target misfit of 113. The inversion took 117 iterations; however, the majority of the decrease in the objective function occurred in the first 25 iterations of the inversion, which decreased the misfit to below 200.

4.4.1Results¶

Figure 4.6 shows the predicted data for this unconstrained joint inversion for all spatially heterogeneous parameters, which has a good visual fit to the the observed data. This figure shows all of the locations and times in a single figure. There are three saturation measurements in the top and bottom layers and two in the middle layer. Over the course of the infiltration experiment, we can differentiate these saturation profiles by the time at which the infiltration front causes an increase in the water content of the soil.

Figure 4.6:Observed and predicted water content data from the one dimensional infiltration experiment showing water content over time.

Figure 4.7 shows the hydraulic conductivity and water retention curves. We allowed each parameter in the van Genuchten curves to vary spatially as shown in Figure 4.8. However, for visualization purposes, Figure 4.7 uses the average value for each parameter type in each layer to calculate the hydraulic conductivity and water retention curves. The amount of the curve that was interrogated by the infiltration experiments is important to consider. As such, the figure also shows the true pressure head values in the entire layer as a normalized histogram. Information about the curves, outside the bounds of the experiment, will likely be poorly estimated. The curves for hydraulic conductivity in the first two layers were well-recovered for the entire domain of pressure head values. Similarly, the water retention curves were well-recovered over the domain of the experiment, as seen in Figure 4.7d and Figure 4.7e. However, outside the pressure head bounds imposed by the experimental setup, which are shown as histograms, the water retention curves were not fit well for pressure head values less than -1.0 m. The recovered curve over-estimated the water content in the top layer and under-estimated it in the middle layer. The third layer was the last to see the effect of the infiltration event and most of the experiment exposed this layer to approximately -0.5 m of pressure head. The recovered curves for the hydraulic conductivity curve are shown in Figure 4.7c, which overestimates the hydraulic conductivity by nearly an order of magnitude at m. Figure 4.7f shows the predicted curve for water retention. Here, the water content is over-estimated at m and under-estimated at m. The location where the layer was sampled was well-recovered and this is seen as the intercept between the true and the predicted models at m, which is the peak of the histogram. In summary, the curves were relatively well-recovered in the first two layers, where the pressure head changed by an order of magnitude over the course of the infiltration experiment. Outside these bounds, the water retention curves were less well-recovered, but the hydraulic conductivity showed a good match. The third layer, however, was not matched well and, outside the bounds of the experiment, the curves for both hydraulic conductivity and water retention were poorly-recovered.

Figure 4.7:Showing the water retention and hydraulic conductivity curves for the true and predicted models for the three soil layers. The histogram in each plot shows the distribution of true pressure head values in each layer.

Figure 4.8 shows the spatially varying van Genuchten parameters through depth. Blue marks the true model parameters and green marks the recovered model parameters at the target misfit. The figure also shows all of the model iterations as thin grey lines of increasing opacity. In Figure 4.8b, the recovered values for appear to fit in the first few iterations of the inversion. The saturated water content in the top layer is recovered to within 0.012 of the true value; the second layer was also well-recovered, with a maximum difference from the true value of 0.016 for the values inside the layer. The saturated water content in the third layer over-estimated the true value by 0.046. The residual water content for all three layers did not move far from the initial estimate and did not recover the difference in the final layer, but underestimated the third layer by 0.040. The majority of the experiment exposed the soil profile to pressures that were between m and m, which is outside the domain where influences the water retention curve, as seen in Figure 4.3. In Figure 4.8d, the parameter did not change from the initial chosen value of 6.0, except in the loam layer where there is a slight increase towards the known value of 9.0. This can be expected from the analysis of the objective functions in Figure 4.4, where could change over a large range without changing the objective function. Figure 4.8a shows the saturated hydraulic conductivity estimate for the soil profile. The estimate shows the layering of the soil profile, which can lead to other parameterization techniques, as we will see in the next section. The top layer is overestimated by up to a 0.34 in -space, the second layer is underestimated by 0.47 in -space, and the third layer overestimates by up to an order of magnitude, 0.98 in -space. The parameter is underestimated in the top layer by a maximum of 0.030, in the second layer is overestimated by a maximum of 0.072, and is slightly overestimated by 0.019 in the third layer.

Figure 4.8:The true and recovered soil parameters as a function of depth, showing (a) hydraulic conductivity; (b) residual and saturated water content; (c) the empirical parameter ; and (d) the empirical parameter . Each plot also shows the full inversion history of the predicted model as a transparent black line.

The parameters estimated by this method demonstrate that the data can be fit by a local minima; that is, multiple values of can sufficiently minimize the water content data provided. Figure 4.9 further highlights this through the plotting of the fields from the recovered model. As expected, the water content field matches the true fields in Figure 4.5, which contains the data that was recorded and fit. There are some oscillations in the top layer due to the estimate of ; these were added in the final iterations of the optimization and could be considered over-fitting of the inversion. We constructed the data from linear interpolation of the closest two cells; the sensitivity to model parameters outside of this interpolation is up to three orders of magnitude lower. When considering a geophysical estimation of water content, the 'footprint' of this estimate should be experimented with because the geophysical estimate is an integration over a certain volume of the soil rather than a point estimate, as is assumed here. Comparing to the true fields for the third layer, the water content profile is well-estimated; however, the pressure head recovery has a completely different character. The middle of the bottom layer reaches a maximum pressure head of -16 cm rather than -27 cm in the true model. Considering that the pressure head range of the experiment was 36.5 cm, this estimate was off by 30.1%; this further shows that only collecting saturation data, especially over a small range of pressure heads, can lead to inaccurate results in both the van Genuchten parameters recovered and the pressure head field.

Figure 4.9:Recovered simulation fields from the unconstrained joint inversion for van Genuchten parameters. Showing (a) the pressure head and (b) the water content over the full time period of the one dimensional recovered soil profile. The soil types are shown as annotations on each figure, the spatial location of water content measurements are shown adjacent to the water content fields.

4.4.2Discussion¶

The recovery of is the most robust in the infiltration experiment considered because the majority of the data was collected when the soil was close to saturation. At these pressure head values, has the greatest control over the van Genuchten water retention curve. We can recover the layering in the system from the saturation data, which can lead to other parameterizations of the model space and exploration of other a priori data to be included. The hydraulic conductivity curves for the first two layers were well-recovered within half an order of magnitude. However, there is a trade-off between and , which could not be isolated over the small pressure ranges that we used for this simulation. We found low sensitivity to over the range of pressure heads investigated, as Mawer et al. (2013) has previously observed. We found a local minima across the , , and parameters. The coverage of a large range (several orders of magnitude) of pressure head values is important for extrapolating the hydraulic conductivity curve and, especially, the water retention curve. Most field studies that use geophysical data to estimate water content will likely see changes of only a few orders of magnitude. However, if only a small portion of the curve is interrogated in the experiment, data can be fit with incorrect van Genuchten parameters. The domain of the curves that is interrogated should be reported with any estimate of van Genuchten parameters. Furthermore, the addition of pressure head data will be advantageous to the joint inversion presented, as it will reduce non-uniqueness in the water retention model for estimating the pressure head field.

4.5Three dimensional inversion¶

In this section, we turn our attention to recovering a three-dimensional soil structure given water content data. The example, motivated by a field experiment introduced in Pidlisecky et al., 2013, shows a time-lapse electrical resistivity tomography survey completed in the base of a managed aquifer recharge pond. The goal of this management practice is to infiltrate water into the subsurface for storage and subsequent recovery. Such projects require input from geology, hydrology, and geophysics to map the hydrostratigraphy, to collect and interpret time-lapse geophysical measurements, and to integrate all results to make predictions and decisions about fluid movement at the site. As such, the hydraulic properties of the aquifer are important to characterize, and information from hydrogeophysical investigations has been demonstrated to inform management practices Pidlisecky et al., 2013. We use this context to motivate both the model domain setup of the following synthetic experiment and the subsequent inversion.

For the inverse problem solved here, we assume that time-lapse water-content information is available at many locations in the subsurface. In reality, water content information may only be available through proxy techniques, such as electrical resistivity methods. These proxy data can be related to hydrogeologic parameters using inversion techniques based solely on the geophysical inputs (cf. Mawer et al. (2013)). For the following numerical experiments, we do not address complications in empirical transformations, such as Archie's equation Archie, 1942. The synthetic numerical model has a domain with dimensions 2.0 m 2.0 m 1.7 m for the , , and dimensions, respectively. The finest discretization used is 4 cm in each direction. We use padding cells to extend the domain of the model (to reduce the effect of boundary conditions in the modelling results). These padding cells extend at a factor of 1.1 in the negative direction. We use an exponentially expanding time discretization with 40 time steps and a total time of 12.3 hours. This choice in discretization leads to a mesh with 1.125 cells in space (). To create a three-dimensionally varying soil structure, we construct a model for this domain using a three-dimensional, uniformly random field, , that is convolved with an anisotropic smoothing kernel for a number of iterations. We create a binary distribution from this random field by splitting the values above and below unity. Figure 4.10 shows the resulting model, which reveals potential flow paths. We then map van Genuchten parameters to this synthetic model as either a sand or a loamy-sand. The van Genuchten parameters for sand are: : 5.83e-05m/s, : 13.8, : 0.02, : 0.417, and : 1.592; and for loamy-sand are: : 1.69e-05m/s, : 11.5, : 0.035, : 0.401, and : 1.474. For this inversion, we are interested in characterizing the soil in three dimensions.

Figure 4.10:Soil structure in three dimensions showing four sections and the boundary between two soil types of sand (yellow) and loamy sand (purple). The two cross-sections and the shallower depth section are shown in subsequent figures.

4.5.1Results¶

For calculation of synthetic data, the initial conditions are a dry soil with a homogeneous pressure head (cm). The boundary conditions applied simulate an infiltration front applied at the top of the model, cm . Neumann (no-flux) boundary conditions are used on the sides of the model domain. Figure 4.13 shows the pressure head and water content fields from the forward simulation. Figure 4.11a and 4.11b show two cross-sections at time 5.2 hours and 10.3 hours of the pressure head field. These figures show true soil type model as an outline, where the inclusions are the less hydraulically-conductive loamy sand. The pressure head field is continuous across soil type boundaries and shows the infiltration moving vertically down in the soil column. We can compute the water content field from the pressure head field using the nonlinear van Genuchten model chosen; Figure 4.11c and 4.11d show this computation at the same times. The loamy sand has a higher relative water content for the same pressure head and the water content field is discontinuous across soil type boundaries, as expected.

Figure 4.11:Vertical cross-sections ( cm) through the pressure head and saturation fields from the numerical simulation at two times: (a) pressure head field at hours and (b) hours; and (c) saturation field at hours and (d) hours. The saturation field plots also show measurement locations and green highlighted regions that are shown in Figure 4.12. The true location of the two soils used are shown with a dashed outline.

The observed data, which will be used for the inversion, is collected from the water content field at the points indicated in both Figure 4.11c and 4.11d. The sampling location and density of this three-dimensional grid within the model domain is similar to the resolution of a 3D electrical resistivity survey. Our implementation supports data as either water content or pressure head; however, proxy water content data is more realistic in this context. Similar to the field example in Pidlisecky et al., 2013, we collect water content data every 18 minutes over the entire simulation, leading to a total of 5000 spatially and temporally extensive measurements. The observed water content data for a single infiltration curve is plotted through depth in Figure 4.12. The green circles in Figure 4.11 show the locations of these water content measurements. The depth of the observation is colour-coded by depth, with the shallow measurements being first to increase in water content over the course of the infiltration experiment. To create the observed dataset, , from the synthetic water content field, 1% Gaussian noise is added to the true water content field. This noise is below what can currently be expected from a proxy geophysical measurement of the water content. However, with the addition of more noise, we must reduce our expectations of our ability to recover the true parameter distributions from the data. In this experiment, we are interested in examining what is possible to recover under the best of circumstances, and therefore have selected a low noise level.

Figure 4.12:Observed and predicted data for five measurements locations at depths from 10 cm to 150 cm from the center of the model domain.

For the inverse problem, we are interested in the distribution of soil types that fits the measured data. We parameterize these soil types using the van Genuchten empirical model (4.2) with as least five spatially distributed properties. Inverting for all 5.625 parameters in this simulation with only 5000 data points is a highly underdetermined problem, and thus there are many possible models that may fit those data. In this 3D example, we will invert solely for saturated hydraulic conductivity and assume that all other van Genuchten parameters are equivalent to the sand; that is, they are parameterized to the incorrect values in the loamy sand. Note that this assumption, while reasonable in practice, will handicap the results, as the van Genuchten curves between these two soils differ. Better results can, of course, be obtained if we assume that the van Genuchten parameters are known; this assumption is unrealistic in practice, which means that we will not be able to recreate the data exactly. However, the distribution of saturated hydraulic conductivity may lead to insights about soil distributions in the subsurface. Figure 4.13 shows the results of the inversion for saturated hydraulic conductivity as a map view slice at 66 cm depth and two vertical sections through the center of the model domain. The recovered model shows good correlation to the true distribution of hydraulic properties, which is superimposed as a dashed outline. Figure 4.12 shows the predicted data overlaid on the true data for five water content measurement points through time; these data are from the center of the model domain and are colour-coded by depth. As seen in Figure 4.12, we do a good job of fitting the majority of the data. However, there is a tendency for the predicted infiltration front to arrive before the observed data, which is especially noticeable at deeper sampling locations. The assumptions put on all other van Genuchten parameters to act as sand, rather than loamy sand, lead to this result.

Figure 4.13:The 3D distributed saturated hydraulic conductivity model recovered from the inversion compared to the (a) synthetic model map view section, using (b) the same map view section, (c) an X-Z cross-section and (d) a Y-Z cross-section. The synthetic model is shown as an outline on all sections, and tie lines are shown on all sections as solid and dashed lines, all location measurements are in centimeters.

4.5.2Scalability of the implicit sensitivity¶

For the forward simulation presented, the Newton root-finding algorithm took 4-12 iterations to converge to a tolerance of m on the pressure head. The inverse problem took 20 iterations of inexact Gauss-Newton with five internal CG iterations used at each iteration. The inversion fell below the target misfit of 5000 at iteration 20 with ; this led to a total of 222 calls to functions to solve the products and . Here, we again note that the Jacobian is neither computed nor stored directly, which makes it possible to run this code on modest computational resources; this is not possible if numerical differentiation or direct computation of the Jacobian is used. For these experiments, we used a single Linux Debian Node on Google Compute Engine (Intel Sandy Bridge, 16 vCPU, 14.4 GB memory) to run the simulations and inversion. The forward problem takes approximately 40 minutes to solve. In this simulation, the dense Jacobian matrix would have 562.5 million elements. If we used a finite difference algorithm to explicitly calculate each of the 1.125e5 columns of the Jacobian with a simple forward difference, we would require a calculation for each model parameter -- or approximately 8.5 years of computational time. Furthermore, we would need to recompute the Jacobian at each iteration of the optimization algorithm. In contrast, if we use the implicit sensitivity algorithm presented in Chapter \ref{ch:richards}, we can solve the entire inverse problem in 34.5 hours.

Table 4.2:Comparison of the memory necessary for storing the dense explicit sensitivity matrix compared to the peak memory used for the implicit sensitivity calculation excluding the matrix solve. The calculations are completed on a variety of mesh sizes for a single distributed parameter () as well as for five distributed van Genuchten model parameters (, and ). Values are reported in gigabytes (GB).

| Mesh Size | Explicit Sensitivity | Implicit Sensitivity | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 parameter | 5 parameters | 1 parameter | 5 parameters | |

| 1.31 | 6.55 | 0.136 | 0.171 | |

| 10.5 | 52.4 | 0.522 | 0.772 | |

| 83.9 | 419 | 3.54 | 4.09 |

Table 4.2 shows the memory required to store the explicit sensitivity matrix for a number of mesh sizes and contrasts them to the memory required to multiply the implicit sensitivity by a vector. These calculations are modifications on the example presented above and use 5000 data points. The memory requirements are calculated for a single distributed parameter () as well as five spatially distributed parameters (, or ). Neither calculation includes the memory required to solve the matrix system, as such, the reported numbers underestimate the actual memory requirements for solving the inverse problem. The aim of this comparison is to demonstrate how the memory requirements scale, an appropriate solver must also be chosen for either method to solve the forward problem. When using an explicitly calculated sensitivity matrix to invert for additional physical properties, the memory footprint increases proportionally to the number of distributed physical properties; this is not the case for the implicit sensitivity calculation. For example, on a mesh, the explicit formation of the sensitivity requires 419 GB for five spatially distributed model parameters, which is five times the requirement for a single distributed model parameter (83.9 GB). For the implicit sensitivity on the same mesh, only 4.09 GB of memory is required, which is 1.2 times the requirement for a single distributed model parameter (3.54 GB). For this mesh, inverting for five spatially distributed parameters requires over 100 times less memory when using the implicit sensitivity algorithm, allowing these calculations to be run on modest computational resources.

4.5.3Discussion¶

In the context of managed aquifer recharge, small variations in soil types can cause differences in infiltration rates. Geophysical data that is both spatially and temporally dense can act as a proxy for water content (cf. Pidlisecky et al. (2013)). If hydraulic properties are identified or even spatially delineated, this knowledge can inform and influence management decisions (e.g. where and when to till or dredge a pond to increase infiltration rates). The hydraulic properties determining these infiltration rates are distributed in three dimensions. The inversion presented above demonstrated a large-scale inversion for a 3D distribution of saturated hydraulic conductivity. We fixed the other van Genuchten parameters at values for sand and, as such, the inversion had difficulty fitting late time data in the deeper profile. The inversion qualitatively discriminated between the two geologic units. In this experimentation, we assumed that the initial conditions and boundary conditions were known. This knowledge may be possible in a heavily monitored situation, such as managed aquifer recharge where the pond water height and underlying water table are measured. Further investigation into the conceptualization of the groundwater simulation is important to both the hydrogeologic modelling and any coupling to geophysical methods Hinnell et al., 2010. The inversion at this scale is computationally possible due to the formulation of the Richards equation presented in Chapter \ref{ch:richards} and the implementation both extended and tested the geophysical inversion framework presented in Chapter \ref{ch:framework}.

4.6Integrations¶

The combination of the Richards equation with geophysical responses has been laid out in Hinnell et al. (2010); this includes both directly coupled and uncoupled forms of integrating information. As presented in Hinnell et al. (2010), uncoupled integrations are completed by: (a) using the geophysical data to estimate a physical property, such as electrical conductivity; (b) using an empirical relation, such as Archie's equation, to transform the geophysical estimate into a hydrological parameter, such as water content; and, (c) using hydrological estimates to help inform or test a hydrogeologic simulation. In contrast, a coupled inversion uses geophysical data to directly inform the hydrogeologic simulation through stochastic or deterministic parameter estimation Finsterle & Kowalsky, 2008Ferré et al., 2009. We can find increasing instances of these sorts of collaborations and studies in near surface hydrogeophysics (cf. Linde & Doetsch (2016) and references within). As data sizes and numerical domains continue to grow, the relatively few parameters that can be estimated by stochastic inversions may not be sufficient. Alternatively, deterministic inversions can be used, but will need to draw on improvements across the field of geophysical inverse problems. For example, regularization techniques using fuzzy c-means clustering, developed in other areas of geophysics, have potential to be helpful in introducing known parameter distributions into the Richards equation inversion Paasche & Tronicke, 2007Sun & Li, 2012. In Hinnell et al. (2010), the authors conclude that, "the coupled approach [for hydrogeophysics] requires that the hydrologic and geophysical models be merged, [which] forces the hydrologist and the geophysicist to formulate a consistent framework," which would require "an uncommon level of collaboration during scientific analysis".

A consistent framework was proposed in Chapter \ref{ch:framework}; however, to both advance leading research and disseminate leading practice, the integration and arbitrary combination of physical simulations must also be possible while simultaneously calculating derivatives efficiently. Appendix \ref{ch:extensions} presents a brief introduction to this collaborative work, as well as several case studies that are striving towards a general formulation. The framework presented in Chapter \ref{ch:framework} has been extended to: (a) explicitly expose assumptions in the forward simulation framework to interrogation and inversion; (b) compose custom objective functions, including regularization and multi-physics data objective functions; and, (c) provide extensible parameterizations that are flexible for custom inclusion of a priori knowledge. This is ongoing, collaborative work.

4.7Conclusions¶

The joint inversion of various hydraulic parameters was explored on a layered 1D soil profile. The water content data was well fit and the soil layers were delineated. Additionally, the van Genuchten curves that were used as the empirical relations were also well recovered over the range of pressure head values that each layer of the soil profile was exposed to over the experiment. Outside of these ranges, the curves were not reliably recovered. As such, the numeric values of the van Genuchten parameters were occasionally unreliable, especially if pressure head was relatively constant, as was the case in the third layer. In this experiment, the water content data was considered as a point measurement, and the sensitivity of the recovered model varied by orders of magnitude between voxels that were included in that measurement and immediate voxel neighbours. This lead to some artificial layering in the recovered model which was not compensated for by the regularization. The footprint of the water content measurement is likely an integration over a number of voxels, especially if coming from a geophysical estimate, and should be considered and experimented with.

As geophysics is more regularly included in hydrogeology parameter estimation the number of distributed parameters that will be necessary to estimate will increase by several orders of magnitude. The final example in this chapter showed a 3D recovery of a distributed hydraulic parameter (). This inversion would not have been possible through standard finite difference techniques and was significantly more memory efficient than an automatic differentiation algorithm that explicitly forms the Jacobian (up to two orders of magnitude in some cases). These improvements allowed the Richards equation inversion to be run on modest computational resources. The coupling, nesting or otherwise integrating of various geophysical methods with the Richards equation is an obvious extension to this work. This has been extensively explored by several authors, albeit at a smaller scale (cf. Linde & Doetsch (2016) and references within). Appendix \ref{ch:extensions} briefly explores various types of integrations between various geophysical methodologies as well as custom model conceptualizations that will be necessary for these integrations.

- Pidlisecky, A., Cockett, a. R., & Knight, R. (2013). Electrical Conductivity Probes for Studying Vadose Zone Processes: Advances in Data Acquisition and Analysis. Vadose Zone Journal, 12(1), 1–12. 10.2136/vzj2012.0073

- Cockett, R., & Pidlisecky, A. (2014). Simulated electrical conductivity response of clogging mechanisms for managed aquifer recharge. Geophysics, 79(2), D81–D89. 10.1190/geo2013-0054.1

- Heagy, L. J., Cockett, R., Kang, S., Rosenkjaer, G. K., & Oldenburg, D. W. (2016). A framework for simulation and inversion in electromagnetics. Computers and Geosciences.

- Cockett, R., Heagy, L. J., & Haber, E. (2017). A numerical method for efficient 3D inversions using Richards equation. arXiv.

- Deiana, R., Cassiani, G., Kemna, A., Villa, A., Bruno, V., & Bagliani, A. (2007). An experiment of non-invasive characterization of the vadose zone via water injection and cross-hole time-lapse geophysical monitoring. Near Surface Geophysics, 183–194.